This article was peer reviewed by Ivan Enderlin and Wern Ancheta. Thanks to all of SitePoint’s peer reviewers for making SitePoint content the best it can be!

Building a simple web application today isn’t that hard. The web development community is friendly, and there are lots of discussions on Stack Overflow or similar platforms, and various sites with lessons and tutorials.

Almost anyone can build an app locally, deploy it to a server, and proudly show it to your friends. I hope you’ve already done all of this, and your project went viral, so you’re obviously here because you want to learn how to make sure your app is ready for some high traffic.

If we think about a web app as a black box, things are quite simple: the app waits for a request, processes it, and returns the response presentation of a resource (HTML, JSON, XML, etc.). One could think: “Yeah, that’s simple, we should be able to scale our app with ease.” Sadly, the world of web development ain’t all sunshine and rainbows, and you’ll encounter a lot of performance issues while your traffic grows! You’ll learn and improve both your skills and the app over time. In this article, designed to speed this process up, I’ll cover the basic concepts of testing the app (regression, load, and stress testing) with Siege and some tips and tricks I like to use when I’m testing my own web apps.

The Types of Testing

Let’s say we want to achieve the daily goal of 1 million unique users. How should we prepare for that amount of traffic? How do we make sure nothing will break under normal traffic or peaks? This type of testing is called load testing, since we know exactly how much traffic we want our app to endure — the load. If you want to push your app to its limits and beyond until it breaks, you’re stress testing your app.

In addition to those, are you aware of how code changes you’ve deployed might affect performance? One simple update can degrade or improve the performance of a high traffic web app to a large extent, and you won’t even know what happened or why until the storm is over. To make sure an app is performing the same before and after a change, we’re doing regression testing.

Another great motivation for regression testing is infrastructure change: for whatever reason, you might want to move from provider A to provider B (or switch from Apache to nginx). You know that your app is usually handling N requests per minute (on average) and what its normal traffic is (a quick look at analytics would do the job). You’re expecting that your app will behave the same (or better) once deployed provider B’s server. Are you sure, though? Would you take that risk? You already have all the data you need, don’t guess! Test your new setup before deploying and sleep better!

Before you start randomly hitting your app with virtual requests, you should know that testing is not an easy job, and the numbers you’ll get from Siege or any other testing tool should be used as a reference to analyze relative changes. Running both Siege and the app locally for five minutes and concluding your app can handle a few hundred or thousand requests within a few seconds is not something I’d recommend.

The Steps for Successful Testing

Plan

Think about what you want to test. and what you expect. How much traffic, on which URLs, with what payload? Define parameters up front, don’t just randomly hit your app.

Prepare

Make sure your environments are as isolated as possible: use the same environment for testing, for every test run. A good guide on how to accomplish this can be found in this book about setting up PHP environments.

Analyze and Learn

Learn something from the numbers and make educated decisions. Results should always be evaluated within their context: don’t jump to conclusions; check everything at least twice.

Getting Started with Siege

Siege is an awesome tool for benchmarking and testing web apps. It simulates concurrent users requesting resources at a given URL (or multiple URLs) and lets the user heavily customize the testing parameters. Run siege --help to see all available options; we’ll cover some of them in detail below.

Preparing the Test App

With Siege, you can test an app’s stability, performance, and improvements between code (or infrastructure) changes. You can also use it to make sure your WordPress website can handle the peak you’re expecting after publishing a viral photo of a cat, or to set up and evaluate the benefits of an HTTP cache system such as Varnish.

For the tests in this article, I’ll be using a slightly modified Symfony Demo application deployed to one Digital Ocean node in Frankfurt, and SIEGE 4.0.2 installed on a second Digital Ocean node in New York.

As I said earlier, it’s crucial to have both the app and test server isolated whenever possible. If you’re running any of them on your local machine, you can’t guarantee the same environment because there are other processes (email client, messaging tools, daemons) running which may affect performance; even with high quality virtual machines like Homestead Improved, resource availability isn’t 100% guaranteed (though these isolated VMs are a valid option if you don’t feel like spending money on the load testing phase of your app).

The Symfony Demo application is pretty simple and fast when used out of the box. In real life, we’re dealing with complex and slow apps, so I decided to add two modules to the sidebar of a single post page: Recent posts (10 latest posts) and Popular posts (10 posts with most comments). By doing so, I’ve added more complexity to the app which is now querying the DB at least three times. The idea is to get as real a situation as possible. The database has been populated with 62,230 dummy articles and ~1,445,505 comments.

Learning the Basics

Running the command siege SOME-URL will make Siege start testing the URL with default parameters. After the initial message …

** Preparing 25 concurrent users for battle.

The server is now under siege…

… the screen will start to fill with information about sent requests. Your immediate reflex would probably be to stop execution by pressing CTRL + C, at which point it will stop testing and give output results.

Before we go on, there is one thing you should keep in mind when testing/benchmarking a web app. Think about the lifecycle of a single HTTP request sent towards the Symfony demo app blog page — /en/blog/. The server will generate an HTTP response with a status 200 (OK) and HTML in the body with content and references to images and other assets (stylesheets, JavaScript files, …). The web browser processes those references, and requests all assets needed to render a web page in the background. How many HTTP requests in total do we need?

To get the answer, let’s ask Siege to run a single test and analyze the result. I’m having my app’s access log open (tail -f var/logs/access.log) in the terminal as I run siege -c=1 --reps=1 http://sfdemo.loc/en/blog/. Basically, I’m telling Siege: “Run test once (–reps=1) with one user (-c=1) for URL http://sfdemo.loc/en/blog/”. I can see the requests in both the log and Siege’s output.

siege -c=1 --reps=1 http://sfdemo.loc/en/blog/

** Preparing 1 concurrent users for battle.

The server is now under siege...

HTTP/1.1 200 1.85 secs: 22367 bytes ==> GET /en/blog/

HTTP/1.1 200 0.17 secs: 2317 bytes ==> GET /js/main.js

HTTP/1.1 200 0.34 secs: 49248 bytes ==> GET /js/bootstrap-tagsinput.min.js

HTTP/1.1 200 0.25 secs: 37955 bytes ==> GET /js/bootstrap-datetimepicker.min.js

HTTP/1.1 200 0.26 secs: 21546 bytes ==> GET /js/highlight.pack.js

HTTP/1.1 200 0.26 secs: 37045 bytes ==> GET /js/bootstrap-3.3.7.min.js

HTTP/1.1 200 0.44 secs: 170649 bytes ==> GET /js/moment.min.js

HTTP/1.1 200 0.36 secs: 85577 bytes ==> GET /js/jquery-2.2.4.min.js

HTTP/1.1 200 0.16 secs: 6160 bytes ==> GET /css/main.css

HTTP/1.1 200 0.18 secs: 4583 bytes ==> GET /css/bootstrap-tagsinput.css

HTTP/1.1 200 0.17 secs: 1616 bytes ==> GET /css/highlight-solarized-light.css

HTTP/1.1 200 0.17 secs: 7771 bytes ==> GET /css/bootstrap-datetimepicker.min.css

HTTP/1.1 200 0.18 secs: 750 bytes ==> GET /css/font-lato.css

HTTP/1.1 200 0.26 secs: 29142 bytes ==> GET /css/font-awesome-4.6.3.min.css

HTTP/1.1 200 0.44 secs: 127246 bytes ==> GET /css/bootstrap-flatly-3.3.7.min.css

Transactions: 15 hits

Availability: 100.00 %

Elapsed time: 5.83 secs

Data transferred: 0.58 MB

Response time: 0.37 secs

Transaction rate: 2.57 trans/sec

Throughput: 0.10 MB/sec

Concurrency: 0.94

Successful transactions: 15

Failed transactions: 0

Longest transaction: 1.85

Shortest transaction: 0.16

The access log looks like this:

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:15 +0000] "GET /en/blog/ HTTP/1.1" 200 22701 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:17 +0000] "GET /js/main.js HTTP/1.1" 200 2602 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:17 +0000] "GET /js/bootstrap-tagsinput.min.js HTTP/1.1" 200 49535 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:17 +0000] "GET /js/bootstrap-datetimepicker.min.js HTTP/1.1" 200 38242 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:18 +0000] "GET /js/highlight.pack.js HTTP/1.1" 200 21833 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:18 +0000] "GET /js/bootstrap-3.3.7.min.js HTTP/1.1" 200 37332 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:18 +0000] "GET /js/moment.min.js HTTP/1.1" 200 170938 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:19 +0000] "GET /js/jquery-2.2.4.min.js HTTP/1.1" 200 85865 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:19 +0000] "GET /css/main.css HTTP/1.1" 200 6432 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:19 +0000] "GET /css/bootstrap-tagsinput.css HTTP/1.1" 200 4855 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:19 +0000] "GET /css/highlight-solarized-light.css HTTP/1.1" 200 1887 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:20 +0000] "GET /css/bootstrap-datetimepicker.min.css HTTP/1.1" 200 8043 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:20 +0000] "GET /css/font-lato.css HTTP/1.1" 200 1020 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:20 +0000] "GET /css/font-awesome-4.6.3.min.css HTTP/1.1" 200 29415 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

107.170.85.171 - - [04/May/2017:05:35:20 +0000] "GET /css/bootstrap-flatly-3.3.7.min.css HTTP/1.1" 200 127521 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (unknown-x86_64-linux-gnu) Siege/4.0.2"

We can see that even though we told Siege to test the URL once, 15 transactions (requests) were executed. If you’re wondering what a transaction is, you should check out the GitHub page:

A transaction is characterized by the server opening a socket for the client, handling a request, serving data over the wire and closing the socket upon completion.

Siege thus won’t only send a single HTTP GET request for the URL provided, it will generate HTTP GET requests for all related assets referenced by the resource at the given URL. We should still be aware that Siege isn’t evaluating JavaScript, therefore AJAX requests aren’t included here. We should also keep in mind that browsers are capable of caching static files (images, fonts, JS files).

This behavior can be changed since version 4.0 by updating the Siege configuration file located at ~/.siege/siege.conf and setting parser = false.

Note: Default behavior may be different depending on the version of Seige you’re using, or even on the tool. If you’re using something other than Siege, check what exactly it considers to be a single test (is it single request for given URL, or a request for a given URL and sub-requests for all its resources?) before you come to conclusions.

From the test output above, we can see that Siege has generated 15 requests (transactions) in ~6 seconds, resulting in 0.58 MB of transferred data with 100% availability or 15/15 successful transactions – “Successful transactions is the number of times the server returned a code less than 400. Accordingly, redirects are considered successful transactions”.

Response time is the average time needed to complete all requests and get responses. Transaction rate and throughput are telling us what the capacity of our app is (how much traffic our app can handle at a given time).

Let’s repeat the test with 15 users:

siege --concurrent=15 --reps=1 sfdemo.loc/en/blog/

Transactions: 225 hits

Availability: 100.00 %

Elapsed time: 6.16 secs

Data transferred: 8.64 MB

Response time: 0.37 secs

Transaction rate: 36.53 trans/sec

Throughput: 1.40 MB/sec

Concurrency: 13.41

Successful transactions: 225

Failed transactions: 0

Longest transaction: 1.74

Shortest transaction: 0.16

By increasing the test load, we’re allowing our app to show its full power. We can see that our app can handle a single request from 15 users on a blog page very well, with an average response time of 0.37 seconds. Siege by default delays requests randomly in the interval from 1 to 3 seconds. By setting the --delay=N parameter, we can affect the randomness of delays between requests (setting the maximum delay).

Concurrency

Concurrency is probably the most confusing result attribute, so let’s explain it. The documentation says:

Concurrency is an average number of simultaneous connections, a number which rises as server performance decreases.

From the FAQ section, we can see how concurrency is calculated:

Concurrency is the total transactions divided by total elapsed time. So if we completed 100 transactions in 10 seconds, our concurrency was 10.00.

Another great explanation of concurrency is available on the official website:

We can illustrate this point with an obvious example. I ran Siege against a two-node clustered website. My concurrency was 6.97. Then I took a node away and ran the same run against the same page. My concurrency rose to 18.33. At the same time, my elapsed time was extended 65%.

Let’s look at it from a different perspective: if you’re a restaurant owner aiming to measure business performance before doing some changes, you could measure the average number of open orders (i.e. orders waiting to be delivered — requests) over time. In the first example above, an average number of open orders was 7, but if you fire half of your kitchen staff (i.e. take a node away), your concurrency will rise to 18. Remember, we’re expecting tests to be conducted in an identical environment, so the number of guests and intensity of ordering should be the same. Waiters can accept orders at a high rate (like web servers can) but processing time is slow, and your kitchen staff (your app) is overloaded and sweating to deliver orders.

Performance Testing with Siege

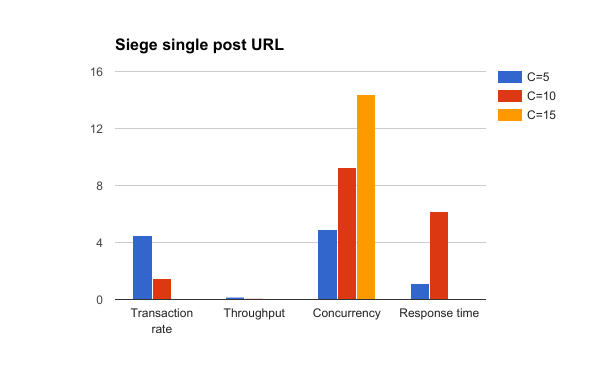

To get a real overview of our app’s performance, I’ll run Siege for 5 minutes with a different number of concurrent users and compare the results. Since the blog home page is a simple endpoint with a single database query, I’ll be testing single post pages in the following tests as they are slower and more complex.

siege --concurrent=5 --time=5M http://sfdemo.loc/en/blog/posts/vero-iusto-fugit-sed-totam.`

While tests are running, I can take a look at top on my app’s server to see the status. MySQL is working hard:

%CPU %MEM TIME+ COMMAND

96.3 53.2 1:23.80 mysqld

That was expected, since every time the app renders a single post page, it’s executing several non-trivial DB queries:

- Fetch article with associated comments.

- Fetch top 10 posts sorted descending by publication time.

- A

SELECTquery with a join between posts and the large comments table withCOUNTto get the 10 most popular articles.

The first test with five concurrent users is done, and the numbers aren’t that impressive:

siege --concurrent=5 --time=5M http://sfdemo.loc/en/blog/posts/vero-iusto-fugit-sed-totam.

Transactions: 1350 hits

Availability: 100.00 %

Elapsed time: 299.54 secs

Data transferred: 51.92 MB

Response time: 1.09 secs

Transaction rate: 4.51 trans/sec

Throughput: 0.17 MB/sec

Concurrency: 4.91

Successful transactions: 1350

Failed transactions: 0

Longest transaction: 15.55

Shortest transaction: 0.16

Siege was able to get 1350 transactions complete in 5 minutes. Since we have 15 transactions/page load, we can easily calculate that our app was able to handle 90 page loads within 5 minutes or 18 page loads / 1 minute or 0,3 page loads / second. We calculate the same by dividing the transaction rate with a number of transactions per page 4,51 / 15 = 0,3.

Well… that’s not such a great throughput, but at least now we know where the bottlenecks are (DB queries) and we have reference to compare with once we optimize our app.

Let’s run a few more tests to see how our app works under more pressure. This time we have the concurrent users set to 10 and within the first few minutes of testing we can see lots of HTTP 500 errors: the app started to fall apart under slightly bigger traffic. Let’s now compare how the app is performing under siege with 5, 10 and 15 concurrent users.

siege --concurrent=10 --time=5M http://sfdemo.loc/en/blog/posts/vero-iusto-fugit-sed-totam.

Lifting the server siege…

Transactions: 450 hits

Availability: 73.89 %

Elapsed time: 299.01 secs

Data transferred: 18.23 MB

Response time: 6.17 secs

Transaction rate: 1.50 trans/sec

Throughput: 0.06 MB/sec

Concurrency: 9.29

Successful transactions: 450

Failed transactions: 159

Longest transaction: 32.68

Shortest transaction: 0.16

siege --concurrent=10 --time=5M http://sfdemo.loc/en/blog/posts/vero-iusto-fugit-sed-totam.

Transactions: 0 hits

Availability: 0.00 %

Elapsed time: 299.36 secs

Data transferred: 2.98 MB

Response time: 0.00 secs

Transaction rate: 0.00 trans/sec

Throughput: 0.01 MB/sec

Concurrency: 14.41

Successful transactions: 0

Failed transactions: 388

Longest transaction: 56.85

Shortest transaction: 0.00

Siege result comparison with concurrency set to 5, 10 and 15

Notice how concurrency rose as our app’s performance was dropping. The app was completely dead under siege with 15 concurrent users — i.e. 15 wild users is all it takes to take your fortress down! We’re engineers, and we’re not going to cry over challenges, we’re going to solve them!

Keep in mind that these tests are automated, and we’re putting our app under pressure. In reality, users aren’t just hitting the refresh button like maniacs, they are processing (i.e. reading) the content you present and therefore some delay between requests exists.

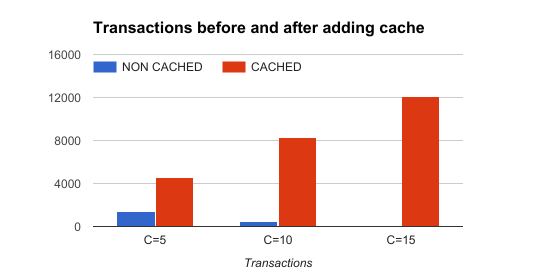

Cache to the Rescue

We’re now aware of some problems with our app — we’re querying the database too much. Do we really need to get the list of popular and recent articles from the database on every single request? Probably not, so we can add a cache layer at the application level (e.g. Redis) and cache a list of popular and recent articles. This article isn’t about caching (for that, see this one), so we’re going to a add full response cache for the single post page.

The demo app already comes with Symfony HTTP Cache enabled, we just need to set the TTL header for the HTTP response we’re returning.

$response->setTtl(60);

Let’s repeat the tests with 5, 10, and 15 concurrent users and see how adding a cache affects the performance. Obviously, we’re expecting app performance to increase after the cache warms up. We’re also waiting at least 1 minute for the cache to expire between the tests.

Note: Be careful with caching, especially IRT protected areas of a web app (oops example) and always remember that it’s one of the two hard things about computer science.

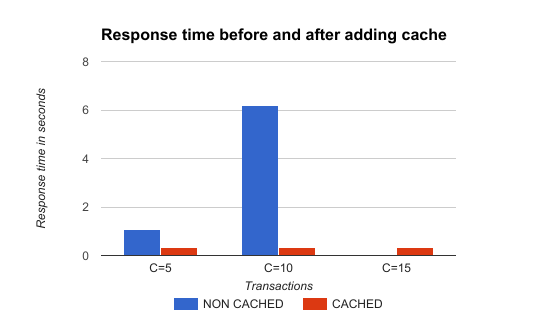

On to results: by adding 60s of cache, the app’s stability and performance improved dramatically. Take a look at the results in the table and charts below.

| C=5 | C=10 | C=15 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transactions | 4566 hits | 8323 hits | 12064 hits |

| Availability | 100.00 % | 100.00 % | 100.00 % |

| Elapsed time | 299.86 secs | 299.06 secs | 299.35 secs |

| Data transferred | 175.62 MB | 320.42 MB | 463.78 MB |

| Response time | 0.31 secs | 0.34 secs | 0.35 secs |

| Transaction rate | 15.23 trans/sec | 27.83 trans/sec | 40.30 trans/sec |

| Throughput | 0.59 MB/sec | 1.07 MB/sec | 1.55 MB/sec |

| Concurrency | 4.74 | 9.51 | 14.31 |

| Successful transactions | 4566 | 8323 | 12064 |

| Failed transactions | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Longest transaction | 4.32 | 5.73 | 4.93 |

Siege of a single post URL with HTTP cache ttl set to 60 seconds

The application was able to handle way more transactions with cache

The response time after adding cache was decreased and stable regardless of traffic, as expected

The Real Feel

If you want to get the real feel of using your app when it is under pressure, you can run Siege and use your app in the browser. Siege will put the app under pressure, and you’ll be able to the actual user experience. Even though this is a subjective method, I think it’s an eye-opening experience for a majority of developers. Try it.

Alternative Tools

Siege isn’t the only tool for load testing and benchmarking of web apps. Let’s quickly test the app with ab.

Ab

ab or Apache HTTP server benchmarking tool is another great tool. It is well documented and has lots of options, though it doesn’t support using URL files, parsing, and requesting referenced assets, nor random delays like Siege does.

If I run ab against single post page (without cache), the result is:

ab -c 5 -t 300 http://sfdemo.loc/en/blog/posts/vero-iusto-fugit-sed-totam.

This is ApacheBench, Version 2.3 <$Revision: 1706008 $>

Copyright 1996 Adam Twiss, Zeus Technology Ltd, http://www.zeustech.net/

Licensed to The Apache Software Foundation, http://www.apache.org/

Benchmarking sfdemo.loc (be patient)

Finished 132 requests

Server Software: Apache/2.4.18

Server Hostname: sfdemo.loc

Server Port: 80

Document Path: /en/blog/posts/vero-iusto-fugit-sed-totam.

Document Length: 23291 bytes

Concurrency Level: 5

Time taken for tests: 300.553 seconds

Complete requests: 132

Failed requests: 0

Total transferred: 3156000 bytes

HTML transferred: 3116985 bytes

Requests per second: 0.44 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 11384.602 [ms] (mean)

Time per request: 2276.920 [ms] (mean, across all concurrent requests)

Transfer rate: 10.25 [Kbytes/sec] received

Connection Times (ms)

min mean[+/-sd] median max

Connect: 81 85 2.0 85 91

Processing: 9376 11038 1085.1 10627 13217

Waiting: 9290 10953 1084.7 10542 13132

Total: 9463 11123 1085.7 10712 13305

Percentage of the requests served within a certain time (ms)

50% 10712

66% 11465

75% 12150

80% 12203

90% 12791

95% 13166

98% 13302

99% 13303

100% 13305 (longest request)

And after we turn cache on, the result is:

ab -c 5 -t 300 http://sfdemo.loc/en/blog/posts/vero-iusto-fugit-sed-totam.

This is ApacheBench, Version 2.3 <$Revision: 1706008 $>

Copyright 1996 Adam Twiss, Zeus Technology Ltd, http://www.zeustech.net/

Licensed to The Apache Software Foundation, http://www.apache.org/

Benchmarking sfdemo.loc (be patient)

Completed 5000 requests

Finished 5373 requests

Server Software: Apache/2.4.18

Server Hostname: sfdemo.loc

Server Port: 80

Document Path: /en/blog/posts/vero-iusto-fugit-sed-totam.

Document Length: 23351 bytes

Concurrency Level: 5

Time taken for tests: 300.024 seconds

Complete requests: 5373

Failed requests: 0

Total transferred: 127278409 bytes

HTML transferred: 125479068 bytes

Requests per second: 17.91 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 279.196 [ms] (mean)

Time per request: 55.839 [ms] (mean, across all concurrent requests)

Transfer rate: 414.28 [Kbytes/sec] received

Connection Times (ms)

min mean[+/-sd] median max

Connect: 81 85 2.1 85 106

Processing: 164 194 434.8 174 13716

Waiting: 83 109 434.8 89 13632

Total: 245 279 434.8 259 13803

Percentage of the requests served within a certain time (ms)

50% 259

66% 262

75% 263

80% 265

90% 268

95% 269

98% 272

99% 278

100% 13803 (longest request)

I love the way ab shows the timing breakdown and stats in the report! I can immediately see that 50% of our requests were served under 259ms (vs 10.712ms without cache) and 99% of them were under 278ms (vs 13.305ms without cache) which is acceptable. Again, the test results are evaluated within their context and relative to the previous state.

Advanced Load Testing with Siege

Now that we have the basics of load and regression testing covered, it is time to take the next step. So far, we were hitting single URLs with generated requests, and we saw that once the response is cached, our app can handle lots of traffic with ease.

In real life, things are a bit more complex: users randomly navigate through the site, visiting URLs and processing the content. The thing I love the most about Siege is the possibility of using a URL file into which I can place multiple URLs to be randomly used during the test.

Step 1: Plan the Test

We need to conduct the relevant test on a list of top URLs visited by our users. The second thing we should consider is the dynamic of users’ behavior — i.e. how fast they click links.

I would create a URL file based on data from my analytics tool or server access log file. One could use access log parsing tools such as Web server access Log Parser to parse Apache access logs, and generate a list of URLs sorted by popularity. I would take the top N (20, 50, 100 …) URLs and place them in the file. If some of the URLs (e.g. landing page or viral article) are visited more often than others, we should adjust the probabilities so that siege requests those URLs more often.

Let say we have following URLs with these visit counts over the last N days:

- Landing page / Home page – 30.000

- Article A – 10.000

- Article B – 2.000

- Article C – 50.000

- About us – 3.000

We can normalize the visits count and get a list like this:

- Landing page / Home page – 32% (30.000 / 95.000)

- Article A – 11% (10.000 / 95.000)

- Article B – 2% (2.000 / 95.000)

- Article C – 52% (50.000 / 95.000)

- About us – 3% (3.000 / 95.000)

Now we can create a URL file with 100 URLs (lines) with 32 x Homepage URLs, 52 x Article C URLs etc. You can shuffle the final file to get more randomness, and save it.

Take the average session time and pages per session from your analytics tool to calculate the average delay between two requests. If average session duration is 2 minutes and users are visiting 8 pages per session on average, simple math gives us an average delay of 15 seconds (120 seconds / 8 pages = 15 seconds / page).

Finally, we disable parsing and requesting of assets as I am caching static files in production and serving them from a different server. As mentioned above, the parser is turned off by setting parser = false in Siege’s config located at ~/.siege/siege.conf

Step 2: Prepare and Run Tests

Since we’re now dealing with randomness, it would be a good idea to increase the duration of test so that we get more relevant results. I will be running Siege for 20 minutes with a maximum delay set to 15 seconds and 50 concurrent users. I will test the blog homepage and 10 articles with different probabilities.

Since I don’t expect that amount of traffic to hit the app with an empty cache, I will warm up the app’s cache by requesting every URL at least once before testing with

siege -b --file=urls.txt -t 30S -c 1

Now we’re ready to put our app under some serious pressure. If we use the --internet switch, Siege will select URL from the file randomly. Without the switch, Siege is selecting URLs sequentially. Let’s start:

siege --file=urls.txt --internet --delay=15 -c 50 -t 30M

Lifting the server siege...

Transactions: 10931 hits

Availability: 98.63 %

Elapsed time: 1799.88 secs

Data transferred: 351.76 MB

Response time: 0.67 secs

Transaction rate: 6.07 trans/sec

Throughput: 0.20 MB/sec

Concurrency: 4.08

Successful transactions: 10931

Failed transactions: 152

Longest transaction: 17.71

Shortest transaction: 0.24

Or with 60 concurrent users during the siege:

siege --file=urls.txt --delay=15 -c 60 -t 30M

Transactions: 12949 hits

Availability: 98.10 %

Elapsed time: 1799.20 secs

Data transferred: 418.04 MB

Response time: 0.69 secs

Transaction rate: 7.20 trans/sec

Throughput: 0.23 MB/sec

Concurrency: 4.99

Successful transactions: 12949

Failed transactions: 251

Longest transaction: 15.75

Shortest transaction: 0.21

We can see that the modified Symfony Demo app (with cache turned on) handled tests pretty well. On average, it was able to serve 7.2 requests per second within 0.7 seconds (note that we’re using a single core Digital Ocean droplet with only 512 MB of RAM). The availability was 98.10% due to 251 out of 13.200 requests having failed (the connection with the DB failed a few times).

Submitting Data with Siege

So far we’ve been sending only HTTP GET requests, which is usually enough to get an overview of an app’s performance. Often, it makes sense to submit data during load tests (e.g. testing API endpoints). With Siege, you can easily send data to your endpoint:

siege --reps=1 -c 1 'http://sfdemo.loc POST foo=bar&baz=bash'

You can also send the data in JSON format. By using --content-type parameter, we can specify the content type of a request.

siege --reps=1 -c 1 --content-type="application/json" 'http://sfdemo.loc POST {"foo":"bar","baz":"bash"}'

We can also change the default user agent with --user-agent="MY USER AGENT" or specify multiple HTTP headers with --header="MY HEADER VALUE".

Siege also can read the payload data from a file:

cat payload.json

{

"foo":"bar",

"baz":"bash"

}

siege --reps=1 -c 1 --content-type="application/json" 'http://sfdemo.loc POST < payload.json'

You can also send cookies within tests by using the --header option:

siege --reps=1 -c 1 --content-type="application/json" --header="Cookie: my_cookie=abc123" 'http://sfdemo.loc POST < payload.json'

Conclusion

Siege is a very powerful tool when it comes to load, stress, and regression testing of a web app. There are plenty of options you can use to make your tests behave as close as possible to a real life environment, which makes Siege my preferred tool over something like ab. You can combine different options Siege provides and even run multiple Siege processes in parallel if you want to test your app thoroughly.

It’s always a good idea to automate the testing process (a simple bash script will do the job) and visualize the results. I usually run multiple Siege processes in parallel testing read-only endpoints (i.e. sending only GET requests) at a high rate and submitting the data (i.e. posting comments, invalidating the cache, etc.) at a lower rate, according to real life ratios. Since you can’t specify dynamic payloads within one Siege test, you can set a bigger delay between two requests and run more Siege commands with different parameters.

I’m also thinking about adding simple load testing to my CI pipeline just to make sure my app’s performance wouldn’t drop below an acceptable level for critical endpoints.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Web App Performance Testing with Siege

What is Siege and why is it used for web app performance testing?

Siege is a free, open-source load testing and benchmarking utility designed to stress test web servers and web applications. It’s used for web app performance testing because it allows developers to measure the load their applications can handle, identify bottlenecks, and determine how their applications behave under different load conditions. Siege supports HTTP/1.0 and 1.1 protocols, GET and POST directives, cookies, transaction logging, and basic authentication.

How do I install Siege on my system?

Siege can be installed on various operating systems. For Linux-based systems, you can use the package manager for your distribution. For example, on Ubuntu, you can use the command sudo apt-get install siege. For macOS, you can use Homebrew with the command brew install siege. For Windows, you can use the Cygwin package manager.

How do I use Siege to perform a simple load test?

To perform a simple load test with Siege, you need to specify the URL of the web application you want to test and the number of concurrent users. For example, the command siege -c5 -t1M http://example.com will simulate 5 users hitting the specified URL for 1 minute.

How can I interpret the results of a Siege load test?

Siege provides a detailed report after each load test, including the total time of the test, the number of hits (requests made), the number of times a request failed, the longest and shortest response time, and the average response time. These metrics can help you understand the performance of your web application under the simulated load.

Can I use Siege to test APIs?

Yes, Siege can be used to test APIs. You can specify the API endpoint as the URL and use the -g flag to perform a GET request or the -p flag to perform a POST request. You can also specify the request headers and body using the -H and -d flags, respectively.

How can I simulate different user behaviors with Siege?

Siege allows you to simulate different user behaviors by using a URLs file. This file contains a list of URLs that Siege will hit in the order they appear in the file. Each URL can be associated with a different HTTP method and POST data, allowing you to simulate different user actions like browsing, searching, and submitting forms.

Can I use Siege for stress testing?

Yes, Siege is an excellent tool for stress testing. By increasing the number of concurrent users and the duration of the test, you can push your web application to its limits and see how it behaves under extreme load conditions.

What are the limitations of Siege?

While Siege is a powerful tool, it has some limitations. It doesn’t support JavaScript, so it can’t simulate user interactions that rely on JavaScript. It also doesn’t support multi-step transactions out of the box, although you can simulate them using a URLs file.

Can I use Siege in a continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) pipeline?

Yes, Siege can be integrated into a CI/CD pipeline. You can run Siege as part of your build process to automatically perform load testing on your web application every time you make changes to it.

Are there alternatives to Siege for web app performance testing?

Yes, there are many alternatives to Siege for web app performance testing, including Apache JMeter, Gatling, and Locust. These tools offer similar features to Siege and may be more suitable for certain use cases. For example, JMeter and Gatling support JavaScript and multi-step transactions, while Locust allows you to write your load tests in Python.

Zoran Antolović is an engineer and problem solver from Croatia. CTO, Startup Owner, writer, motivational speaker and usually the good guy. He adores productivity, hates distractions and sometimes overengineers things.